Network security and privacy largely rely on a set of well-known and well-defined protocols: TLS/SSL, SSH, Kerberos, etc. Billions of people and devices rely on and have inherent trust in these protocols. Why? They've been told that these designs are secure. A smaller, yet still substantial subset, refuses to trust these systems for any number of reasons. Perhaps the government made them, or perhaps they fear corporate interests will invade their lives. Both sides stem from a root issue: the inaccessibility of cryptography to the layman. Cryptography is difficult to understand, leading to either blind trust or extreme mistrust in any given protocol.

Cryptosystems are validated through rigorous, repeated testing, long-term use, and formal verification. Formal verification is "the act of proving the correctness of algorithms with respect to a certain formal specification or property, using formal methods of mathematics." But, unfortunately, these verification methods tend to be computationally expensive and time-consuming, while requiring extensive knowledge about cryptosystems and seemingly unknowable math pitfalls.

With this blind trust and mistrust of cryptography and the existing difficulty in explaining and testing these systems and their intricacies to the layman, how does one make the formal verification of cryptographic protocols easy to understand, implement, verify, and reproduce?

What is Verifpal?

Verifpal is an "automated modeling framework and verifier for cryptographic protocols, optimized with heuristics for common-case protocol specifications, that aims to work better for real-world practitioners, students, and engineers without sacrificing comprehensive formal verification features"[1]. It is a modeling framework for networks and other cryptographic protocols that is easy to learn, use, and design without requiring an extremely in-depth knowledge of cryptography. It has already been used to verify a number of protocols, including Signals' Double Ratchet and Scuttlebutt.

There are two major models of verification: symbolic and computational. Symbolic models verify through the interactions of symbols, while computation models verify through computation. Verifpal is a symbolic model and thus cannot verify the computational security of a system. But, given that one of the core pillars of Verifpal is its emphasis on usable and understandable design, this choice of model makes perfect sense. Symbolic models use symbols to represent complex ideas in an easy-to understand form, abstracting away the complexities of cryptography.

Symbolic Methods

There are numerous available methods for symbolically verifying a system. While it is not information that is needed, it is good to give a rough definition to some of the techniques used by Verifpal and others to break down protocols. These methods, and the others that are used, expose weaknesses through different aspects of symbolic analysis.

- Unbounded Execution - Can the tool test systems where there can be an infinite number of sessions?

- Equational Theory - Test that actions (equations) are equal to one another.

- Mutable Principal States - Can the tool model objects with mutable states?

- Equivalence Properties - Test that both sides of a protocol conduct the same actions in exchange.

- Link Properties - Can the tool generate code to link symbolic security guarantees to real-world implementations?

See [2] for further details.

Existing Verification Systems

Verifpal was built as an alternative in a heavily populated environment of competing verification tools. Many of the existing tools were cited as being bulky, complicated, and hard to use, requiring a decent background in math and cryptography that Verifpal wanted to avoid.

A short list of existing tools: - Symbolic - CPSA (Cryptographic Protocol Shapes Analyzer) - DEEPSPEC (Deciding Equivalence Properties in Security Protocols) - ProVerif - Tamarian - Computational - CryptoVerif

Programming in Verifpal

Verifpal has a simple and compact language, requiring knowledge of only a few key definitions before diving in. Listed below are the important terms for this reading, but is by no means a complete list.

- Principal - A participant in a cryptographic exchange (i.e. Bob or Alice).

- Attacker - A passive or active actor maliciously listening to or interfering with an exchange.

- Knows - A principal has prior knowledge of a value.

- Leaks - Attacker has immediate knowledge of a value.

- Primitive - Built in, atomic cryptographic functions.

- Explosive Primitive - Primitives where the possible combinations of states and values grows too quickly to allow reasonable program termination.

- Queries - Test aspects of confidentiality, authentication, and integrity.

See [3] for further details.

Stages of Execution

Verifpal runs in "stages" of execution, which each stage accomplishing a different goal.

Stage 0 - Attacker can only passively listen. Stage 1 - Stage 0 plus equation exponents may be mutated to nil (i.e. ENC(key, data) can become ENC(nil, data)). Stage 2 - Stage 1 plus non-explosive primitives can be mutated. Stage 3 - Stage 2 plus the addition of explosive primitives. Stage 4 - Stage 3 plus the ability to replace constants and equation exponents with one another. Stage 4+ - Stage 4 plus an allowed mutation depth of n - 3 where n is the current stage (i.e. HASH(x) can become HASH(HASH(y))).

Simple Example

Let's walkthrough a simple example, taken from Verifpal's included samples[4].

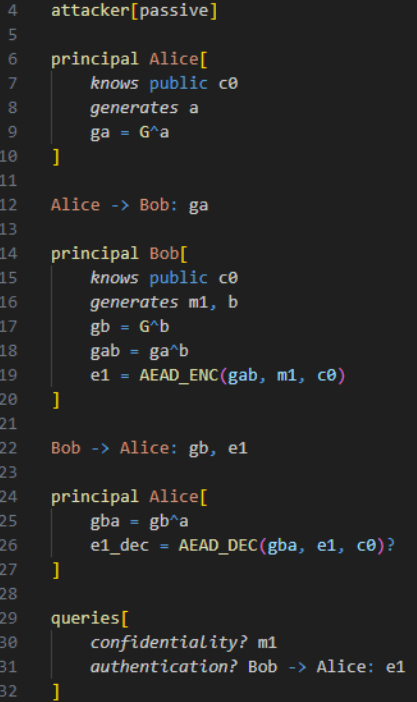

First, a passive attacker is defined. A principal, Alice, is defined. She knows some public data, c0. Given that c0 is public, the attacker knows it as well. She also generates a value, a. Using a, a public Diffie-Hellman key, ga, is created. G is a special value used for Diffie-Hellman exponentiation.

With the attacker and Alice defined, Alice proceeds to send Bob ga using the notation seen on line 12. This act of sending data also means the attacker now has ga.

A new principal is defined as Bob, who receives ga. He also knows the public value c0 and generates two values, m1 and b. m1 is the message Bob wants to give Alice. b is used to generate gb, his Diffie-Hellman key. ga is also used with b to create the shared secret, gab. Using this shared secret, Bob encrypts m1 with some associated data, c0. The associated data serves as unencrypted but tamper-resistant data. Finally, Bob sends Alice gb and the newly encrypted message e1. Now Alice can create the shared secret as well and use it to decrypt the message from Bob. \

With the exchange completed, we can ask Verifpal to verify confidentiality and authentication for specific variables in the system. Specifically, we want to ensure the confidentiality of m1 and that an attacker cannot impersonate Bob to Alice when sending e1.

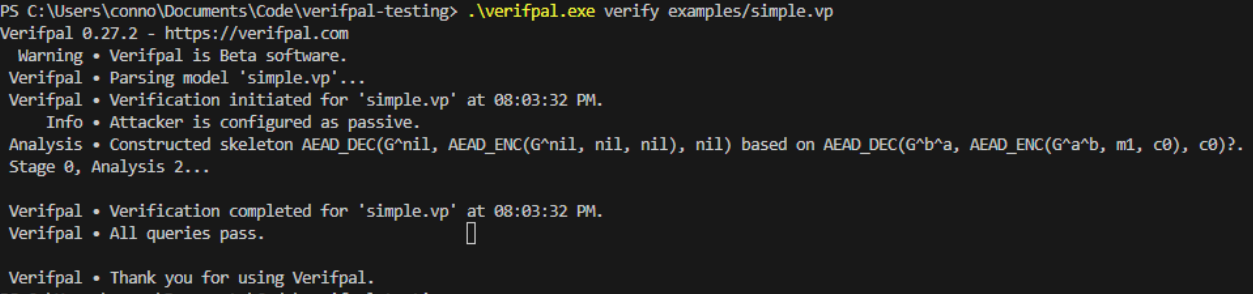

Running Verifpal over the example with a passive attacker yields no issues, with all queries passing. There is a single line of analysis based on the information the attacker had, but it was unable to successfully attack the system.

Now that's all well and good, but what about an active attacker? An active attacker not only passively listens but also injects, replays, and edits exchanged information.

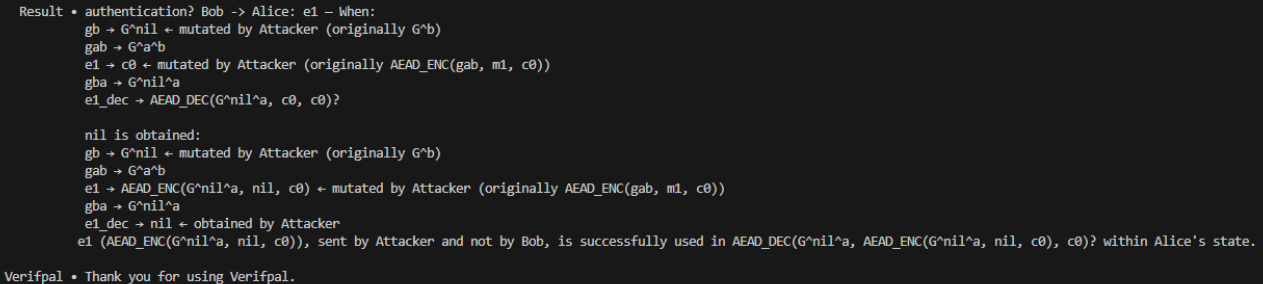

Alas, the exchange was not as secure as it first seemed! Running with an active attacker illuminated two possible attacks, as shown by the "Result" header. With the first, Verifpal found that the confidentiality of m1 was lost when the attacker set up a man-in-the-middle to intercept and manipulate key material. In the second attack, the attacker was able to impersonate Bob to Alice by again manipulating key material in a man-in-the-middle.

As we can see, Verifpal provides a simple yet informative interface for testing cryptographic systems for design flaws. Now let's use Verifpal to test something a little more novel.

Off The Record Messaging Protocol

The internet is made up of a couple pretty ubiquitous protocols. The protocol I chose to implement and test in Verifpal is a bit more esoteric. Off the Record (OTR) Messaging Protocol is an instant messaging protocol designed to provide deniable authentication so that an attacker can't prove the sender and recipient were involved in an exchange (hence "off the record"). This is an application layer protocol split into two phases: authenticated key exchange (AKE) and data exchange.

I set out to answer three specific questions: 1. How does the system fare against a passive attacker? 2. How does the system fare against an active attacker? 3. What data can we leak from the system before it becomes unusable?

It's worth noting that the OTR protocol specification leaves some ambiguity on specific elements of the implementation. A particular favorite was "Computes two AES keys c, c' and four MAC keys m1, m1', m2, m2' by hashing s in various ways." What do various ways mean? I took it to mean a different salt for each, but it's open to interpretation[5].

Implementing OTR in Verifpal

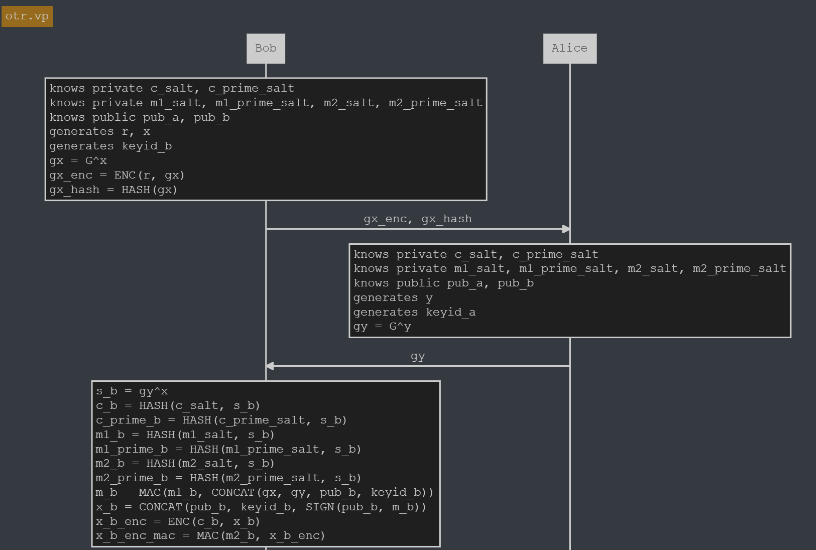

Verifpal gives a very nice overview of exchanges, which will be used to show the exchange more clearly. It is not important to fully understand the details of this exchange, but I wanted to provide a full overview regardless.

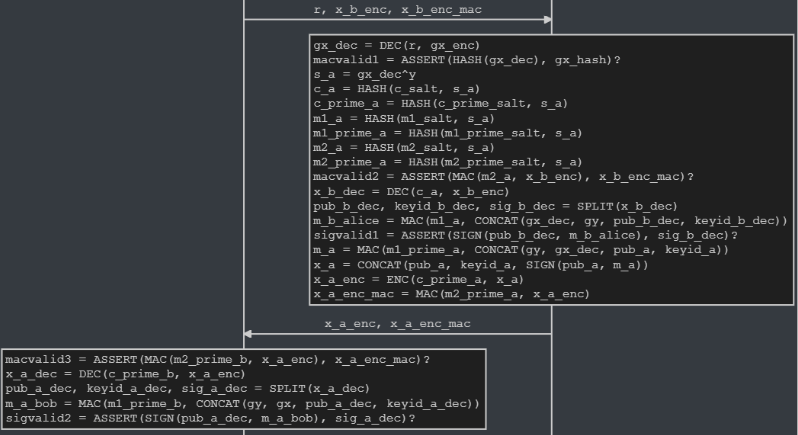

Alice and Bob have six predefined private salt values for deriving AES and MAC keys. They also know each other's long-term public keys. Bob generates a key, r, along with his Diffie-Hellman key, gx, which he encrypts with r. The encrypted value gx_enc is hashed and stored in gx_hash. Both gx_enc and gx_hash are then sent to Alice.

Alice generates her Diffie-Hellman key, gy, and sends it to Bob. Bob is then able to use this information to create his shared secret, s_b. He proceeds to create a message with all his key material, sign it with his public key, and then encrypt it with one of the derived keys. He finally hashes this encrypted value. Bob then sends the plaintext r value and the encrypted key information to Alice.

Alice proceeds to generate her derived keys, which will be the same as Bob's. She next verifies the authentication and integrity of Bob's message. Finally, she creates a message with all her key material in the same manner as Bob and sends it to him. Bob verifies the information, ending the AKE.

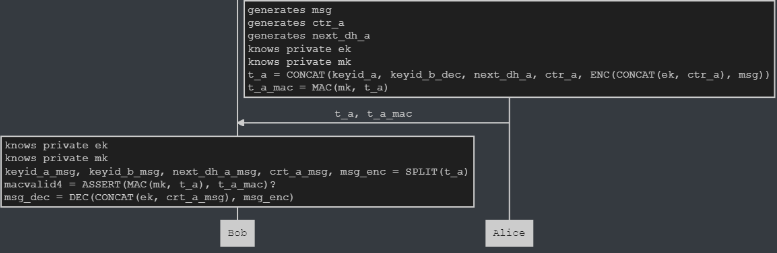

Now starts the message segment. Alice generates a message, a counter, and a new Diffie-Hellman key. Bob and Alice each generate an ephemeral and message key based on previous key information. This process could not be replicated in Verifpal, being replaced with just a "generates" command for the time being. Alice encrypts the message using the ephemeral key and the counter and sends this, along with some key information, to Bob. Bob verifies the MAC and decrypts with the received counter information and his derived ephemeral key.

OTR Results

Passive Attacker

The analysis for a passive attacker was expectedly uninteresting. Verifpal was asked to verify the confidentiality of the final message between Alice and Bob and the authentication of T_A, the key material Alice sent Bob with the message. Confidentiality and authentication were held against the attacker.

Woes of Math (and Time)

Before we can talk about the results for the active attacker, we need to talk about computation. Remember Verifpal's stages of execution, specifically stages 3+, which allow the inclusion of explosive primitives? Stage 4+ allows mutation of those primitives with a depth of n - 3. There are a lot of potential variations on a single primitive. The first implementation of OTR in Verifpal had 54 different primitives. Some quick, very rough, pencil and paper math yielded approximately 240 million runs required for the simulation. The system running the test had an i7 with 8 cores and 16 threads. Verifpal is multi-threaded. The first run took a week before it was aborted. The second run took four days before Windows Update decided it was time to reboot. The third run was given a week, to no avail. At a pace of about 10 million iterations per day, it was going to take far more than a week to run a single simulation. At this point, I was asking myself if the implementation could be simplified.

Simplifying the Algorithm

Improving the execution speed came down to reducing the number of primitives in the model. This was done through several measures: 1. The calculation of derived keys through hashing was replaced with known private constants. 2. Removed the message exchange, leaving only the AKE.

Verifpal could no longer learn that the derived keys come from s, but it was unfortunately necessary to get a runnable model.

Active Attacker

Due to the modifications, the Verifpal queries changed from the passive attacker. Now, Verifpal was asked to verify the confidentiality of the shared secret, s, and the authentication of Alice's and Bob's encrypted key information sent during the AKE. This model took about 24 hours to run.

The confidentiality of the shared key was also not ensured. The attacker was able to manipulate Alice's half of the modified Diffie-Hellman exchange to trivialize the computation of the shared key. Authentication was also broken as the attacker was able to impersonate Alice to Bob via replay attacks.

Discussion

Unfortunately, despite the interesting results, these results must be taken with a grain of salt due to not being a pure representation of what OTR should be in Verifpal. Some aspects, such as the Diffie-Hellman shared key creation, can be tested, but other aspects, like key derivation, cannot.

The big issue is Verifpal "dumbs down" the implementation of cryptographic protocols. This abstracts away from important concepts like XOR, bit shifting, rotations, and utilizing specific bits of a value. It can make the implementation of simple protocols easier, but it does make the implementation of more complicated protocols much harder. OTR uses specific bits from various values to create the ephemeral key in the data exchange, something that just can't be modeled in Verifpal but can in other tools, such as ProVerif.

Conclusions

This research explored Verifpal's capabilities and shortcomings, culminating in the implementation of a variation of Off the Record Messaging Protocol. Using Verifpal on this model, it identified potential Diffie-Hellman implementation and replay attack issues in the Authenticated Key Exchange.

While Verifpal certainly makes putting together a model easier for the layman, the computation requirements can present a challenge for developers in the field. Additionally, while Verifpal provides a fantastic format for the layman to formally verify protocols, it struggles to provide an interface to implement complex and intricate key derivation techniques.

References

- [1] N. Kobeissi, G. Nicolas, and M. Tiwari, "Verifpal: Cryptographic Protocol Analysis for the Real World," https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/971.pdf.

- [2] M. Barbosa et al., "Sok: Computer-Aided Cryptography," https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/1393.pdf.

- [3] N. Kobeissi, Verifpal User Manual, 1st ed.

- [4] N. Kobeissi, examples/simple.vp, https://github.com/symbolicsoft/verifpal/blob/master/examples/simple.vp.

- [5] "Off-the-Record Messaging Protocol version 3," Off-the-record messaging protocol version 3, https://otr.cypherpunks.ca/Protocol-v3-4.1.1.html.